When I was a kid, 16 color EGA (Enhanced Graphics Adapter) graphics games had already hit the shelf. However, because our home computer was a very old IBM PC, I had to resort playing games in CGA. CGA (or Color Graphics Adapter) had only 4 colors. Many people would probably consider it as extremely ugly. I should know, because I was in utter dismay when the prince in Prince of Persia had pink skin.

Ugly colors graphics as it indeed was, the 4 color palette did become a milestone in my computer gaming life. Because just before CGA, I first saw computer games as green monochrome pixels on the Apple II. When 4 miserable colors showed up, hey, they were still colors. As a young kid, having 4 colors instead of one, and yet having a glimpse the “future” in the form of EGA, it gave me sufficient data to extrapolate how gaming can evolve. This helped to stretch my imagination a little bit and thus probably started my curiosity in game development.

But before we get there, CGA itself has its charm. CGA graphics was a brutally honest reflection about how games are in fact a digital manifestation of the human imagination. No matter how well one attempts to make a game realistic, the game will always fall short of reality. I remember an era when games attempt to break this barrier (and even so today), but to me, its greatest glory is to swagger down the beach to say that it isn’t trying to do so. A CGA game said this to me: I am not going to pretend that I am realistic at all. Heck, look at my colors. I am a game. Therefore, have fun.

And fun I did have. With that, I recently started exploring the idea of deliberately creating indie games in CGA colors.

Leaving a lot of room for the imagination

The pink Prince of Persia was not a good example. Prince looked best in EGA or VGA in my honest opinion. But games like Alley Cat, Archon and Sopwith (non-exhaustive list) had their charm in CGA. With extremely low quality graphics and colors, The player is presented with a lot of visual gaps of what he or she is seeing. As a result, the mind focuses on the game play, and also fills visual gaps with imagination.

For example, for Sopwith, colors added some visual depth and separation of game entities. It made me as a kid believe far enough that I was in a digital world which was not the same as the physical one we are in, and this digital world had some “life” in it. I could not see the pilot in the plane, neither the soldiers in the tank, but boy did I image them being there.

The lack of colors also helped me imagine how it would have been like, should games eventually have more colors. The Prince of Persia intro screen in CGA was actually quite beautiful (see video in the first paragraph). And because EGA graphics already existed at that time, it was easy to look at both graphics and recognize the exponential development that would radically change the visuals of newer games. This idea perhaps fueled my imagination a lot more whenever I saw CGA graphics. I got to imagine what the future of a sequel might be.

The niche appeal of only 4 colors

Monochrome has extremely limited options. As such, visual options are usually confined to very limited visual styles and perhaps more focus on text and typography. This is not necessarily a bad thing as it brings a certain novelty that probably cannot be derived in any other way.

Likewise, CGA art sets a limitation of creative options, but also carves its own appreciation niche. In contrast to monochrome, having 4 colors is sufficient to differentiate game entities and introduce depth. Coupled with modern physics and memory capabilities for fluid action, a decent rebirth is possible. One such example is the game The Eternal Castle [REMASTERED]. I have never seen a more beautifully rendered CGA graphics game with modern game mechanics yet.

The Eternal Castle [REMASTERED] faithfully kept to the limited CGA colors1, and also maintained its blocky pixels. However, it incorporates modern animation in the form of shattering glass particles and post-processed 3D rendered backgrounds.

But as you probably notice, the limitation of colors did add to the charm and experience. The gamer understands the context with the sufficient detail provided. Then the gamer creates his or her own further interpretation on the missing visual gaps.

1 For an excellent technical explanation about CGA colors and palettes, watch this very informative video by The 8-bit Guy.

Where can we go with CGA in indie games?

I would probably be one of the first to say that not all games will look good in CGA. And if CGA becomes mainstream or become an overused novelty, then it will lose the novelty itself (imagine a flood of CGA games on all genre on Steam… no…). However, I’d like to encourage us as game developers to experiment with it for creative exercise.

As I said earlier, a pink Prince of Persia was awful. This was a classic example, at least to me, of not when to choose CGA as a theme. But if the character is of an acceptable black silhouette or a deliberately creepy cyan humanoid creature form, then yes CGA may be suitable.

Exploring games with CGA in mind can also help force out graphic distractions and focus on the game play, mechanics and perhaps also the plot, if relevant. Game developers commonly use powerful graphics to mask other poor areas of development. And as gamers, what we want is a good game, not merely an interactive medium (there is a place for such products, but that is just not within the context of this article).

Indie game developers have done it before

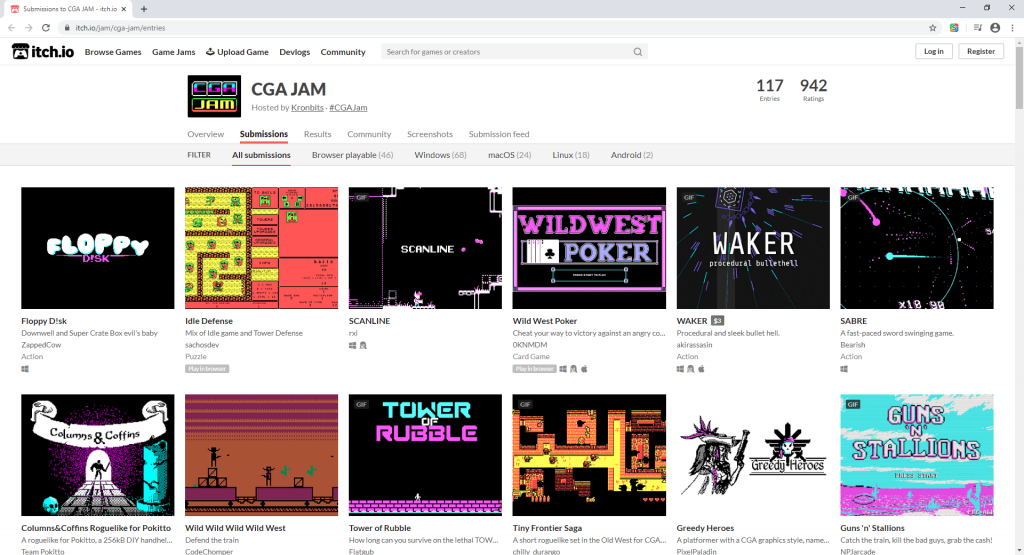

In 2017, Spanish indie game developer Davit Masia (now known as Kronbits) threw a CGA game jam on itch.io. The response was successful. 136 entries were posted during the two-week game jam submission period (check them out here).

About CGA graphics, Masia said, “I think color restrictions are good for creativity and help to improve art skills—or simply for fun, to see what you can do with such limitations.” source

There are also CGA graphics indie games on Steam like Mazebot, Arctic Adventure, Detonation and Speakerman. You can check them out here.

This article isn’t a call for departing from modern graphics back into CGA, but a reminder that rich graphics does not make a great game. A great game is simply great, because as a game itself, it is great.

Further image credits: GameSpot